by Çağıl Çayır – Historian

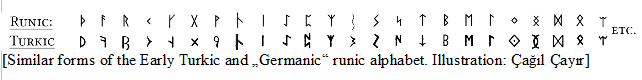

Most people are familiar with the runic script from Europe as the script of the „Germanic“ peoples. The Old Turkic script from Siberia and Mongolia, on the other hand, which is characteristically similar to the European runes, is known to very few people. Even those who study the Old Turkic script scientifically usually know nothing about the great need for comparison – or deny it!

In order to explain and propose the current need for research on the comparison of early Turkic and „Germanic“ (about the term „Germanic“) script and culture, it is advisable to start with the earliest knowledge and trace the history of the reception of the scripts and cultures up to the present day.

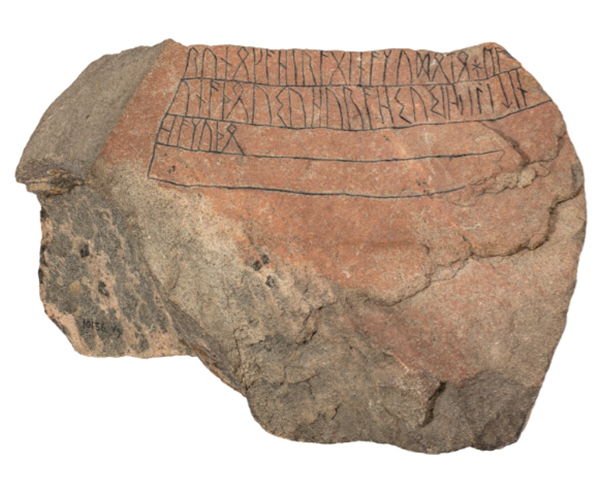

[„Runes from the gods I write…“ The Noleby inscription probably dates from around 600. Photo: Helena Bonnevier, Swedish National Historical Museum (CC BY 4.0)]

Let’s start with the rune writers from Europe. They have mostly only handed down short inscriptions to us, which are barely decipherable to this day. This is why we hardly know anything about the world of the rune writers from the rune writers themselves. It was only with the adoption of Christianity and the Latin alphabet that the oral traditions of the Germanic tribes, where the rune script was widespread, were written down.

The Franks offer us the first insight into the origin myths of the Germanic tribes. In the 7th century, the Franks themselves told that they came, together with the Turks, from Troy. This legend of the kinship between Franks and Turks became popular in the course of the Crusades and the encounter between the Frankish Crusaders and Muslim Turks in the „Holy Land“. The earliest origin myth of the Icelanders also dates from this time.

Just as the first Icelandic historian Ari Thorgilsson derived his family tree from a Turkish King (Tyrjka konungr), his successor, the most precious skald (poet) and historian Snorri Sturluson, writes in his Old Norse textbook „Edda“ and Old Norse kings‘ sagas „Heimskringla“ from the 13th century that Odin, who is known for finding the runes from the „Poetic Edda“, was a Turkish King from Asia. So the name of the Turks was known in Europe from the 7th century, at latest, either as relatives of the Franks or as ancestors of the Icelanders and thus indirectly, through the mythology of the runic script and Odin, as the inventors and teachers of runic writing in Europe.

[The oldest Odin inscription was recently found in Vindelev in Denmark and dates back to the 5th century. Highly remarkable are besides the runic inscription, the rider with the long, braided hair, the decorated horse, the svastika and the so-called torque, which were also part of the early Turkic costume, art and culture. Photo: Vejl Museums (CC BY 4.0)

However, with the increasing power of the Ottomans, this kinship became troublesome and was broken and suppressed. At the latest, after the Ottomans conquered Constantinople in 1453. Enea Silvio Piccolomini, then still a cardinal, was one of the greatest advocates of a new crusade against the Turks. He immediatly began to call for a new „Holy War“ against the Turks. And in this sense he displaced and denied the traditional European myths of common origin and kinship with the Turks.

According to Piccolomini, the Turks could not be relatives of the Europeans and certainly could not have come from Troy anymore, as it was generally assumed even until the 16th century. In „reality“, he claimed, the Turks would be eternal strangers and enemies of the Europeans. He also equated the originally called Deutsch people of his time with the ancient „Germans“ of Ceaser and Tacitus. To the surprise it was also Piccolomini, who suddenly discovered the over one and a half millenia lost manuscript of Tacitus‘ Germania at exactly this time and used it politically from the outset – not to say abused it.

In 1454 in Frankfurt, Piccolomini told the Deutsche (later called German) listeners for the first time that they had not mixed with anyone and had not immigrated from anywhere, but were the „pure“, unmixed natives of Europe – and were now called upon to defend the „heritage of their ancestors“ in the face of the impending danger from the now supposedly eternal foreigners and enemies from Asia, the Ottomans – the Turks.

The Romanocentrism of the Italians, however, provoked the now called „German“ humanists to form their own image of „Germany“, instead of holding on to their traditional Asian, Turkish and Trojan origin myth. The Germanocentrism in Germany in turn motivated the Scandinavians to promote an early Scandinavism, with recourse to the runic monuments in Sweden and Denmark. It was at this time that modern runic research began, which was also determined by power politics and patriotic ideologies from the outset.

So after Christianity first displaced runic writing and its pagan culture in Europe, paradoxically the Roman churchs propaganda for a new „Holy War“ against the Turks effected indirectly the Scandinavians to ideologize the monuments of the Pre-Christian era again. Thereby one was still not averse to considering an oriental origin for the runes – but according to the Bible instead of the written legend of a Turkish origin.

However, even this was soon superseded by the wishful thinking that the Swedes were the inventors of runic writing and that all human civilisations had emigrated from Sweden to the rest of the world.

The so-called Swedish „Rudbeckianism“ was first defeated violently in the 18th century by the Great Northern War. During this war, tens of thousands of Swedish soldiers became prisoners of war and were deported to Siberia.

It was there that the German-born officer in the Swedish army Philipp Johann Tabbert, later von Strahlenberg, discovered the first runic monuments in Siberia together with Daniel Gottlieb Messerschmidt, a German doctor from Danzig commissioned by Peter the Great.

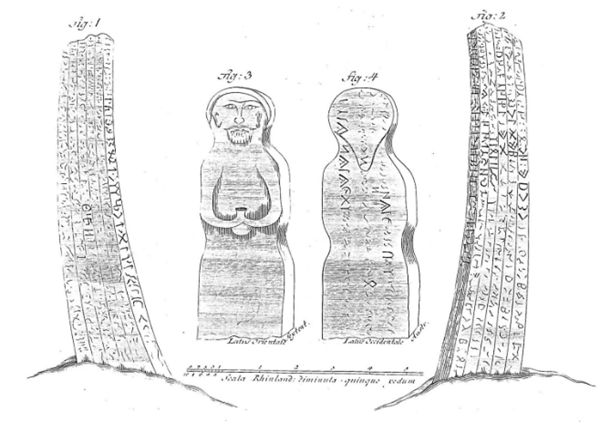

[Drawing of the first rune finds from the region around Abakan in Siberia. Drawn on site by Karl Schulmann in 1721 and published by Gottlieb Siegfried Bayer in 1729.]

This finding reminded the scholars in Europe of the old migration legends. An Asian and Turkish origin and kinship of the European people was once again considered. This view can be found among the greatest scholars of the 18th and 19th centuries. Such as Wilhelm Grimm and Carl Ritter. However, such discussions could not prevail against the worldview of their time – such as hatred against Turks and racism. Wrongly, it was even repeatedly claimed that no runic inscriptions had been found in Siberia. Therefore in the 19th century the opinion became established that runic monuments had only been found in Europe. So the Siberian runes become excluded, ignoreded, neglected and forgotten.

But, in 1821, for example, the founder of scientific runic research, Wilhelm Carl Grimm, argued that the runic script may well have been brought to Europe from Siberia, „the former homeland“ of the Germans. In this respect, he found the Siberian monuments most interesting:

„[…] one can by no means call the hope of obtaining further information about the runes from Asia vain. In this respect, the inscriptions on gravestones on the Yenisei River in Siberia […] are most remarkable.“

[Wilhelm Carl Grimm, Über deutsche Runen, Göttingen 1821, p. 127.]

At that time, the Siberian runic monuments had not yet been deciphered and, as already mentioned, the findings were repeatedly denied and forgotten. This went so far that even Ludwig Wimmer, the innovator of scientific runic research after Grimm, at the end of the 19th century, around 1870, still pointed out the theoretically enormously important need for comparison with runes from the East, but wrongly claimed that no traces of runic writing had yet been found in whole Russia, including Siberia. Therefore he wrongly eliminated the Eastern horizon and directed the runic research to the limits of the European continent.

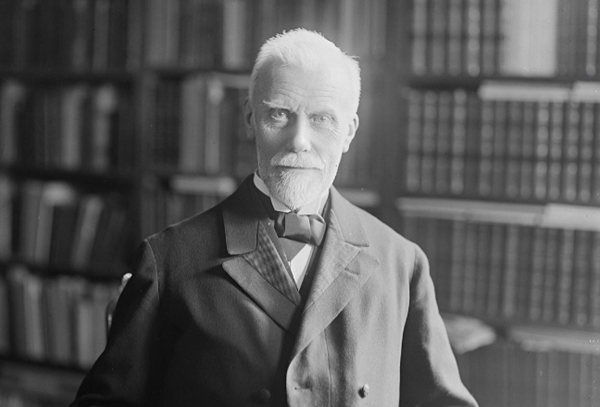

[Vilhelm Thomsen deciphered the Old Turkic script from Mongolia and Siberia in Copenhagen, Denmark in 1893. Photo: Peter Elfelt (CC BY 4.0)]

Ironically, it was Wimmers colleague from Copenhagen, Vilhelm Thomsen, who deciphered the runic script from Siberia and Mongolia as Old Turkic in 1893. However, contrary to the many previous assumptions and impulses to compare the runes in East and West, Thomsen suddenly suggested that the Old Turkic and European runic monuments could be just coincidentally similar.

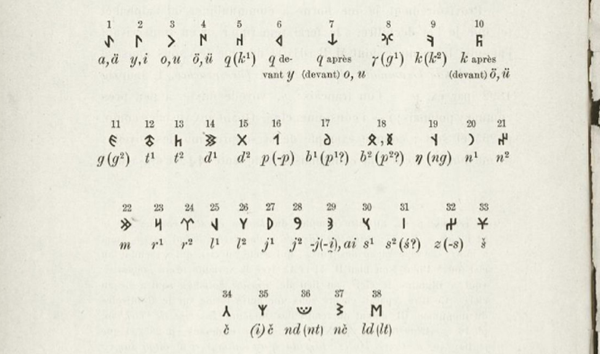

[The Old Turkic alphabet, Source: Vilhelm Thomsen, Déchiffrement des Inscriptions de L’Orkhon et de L’Iénnisei. Notice préliminaire. Extrait du Bulletin de L’Académie Royale des Sciences et des Lettres de Danemark 1893, Copenhague 1896, p. 14.]

This assumption then became a „fact“ without further investigation and manifested the prejudiced separation of scripts and cultures in science and society, which ultimately paved the way for the racial ideological perversion of the European runes by the National Socialists in Germany. The Nazis disarrayed the runic script to the most important evidence and witness of their racial ideology, which mentally prepared, carried and accompanied the Nazi crimes and Holocaust.

Like the „Nordic“ ideological exeggeration of the history in Sweden was violently ended by the Great Nordic War, also the „Germanic“ ideological perversion of runic writing in Germany was ended violently by the Second World War. After that, the runic script fell into the shadow of its abuse and was, so to speak, a taboo subject. After 1945 hardly any German scientist dared to pick up the runic script again. It was not until the turn of the millennium that runic research reached a new stage.

It is no longer assumed that the runes had a purely „Germanic“ origin, but rather that the runic script was modeled on the Latin, Greek, Etruscan or Phoenician script. However, the Turkic and Siberian theory of origin, which is based on Old Norse legends and has been frequently proposed in the history of research, continues to be neglected and, as mentioned at the beginning, even denied…

Yet, in addition to science, the comparison of scripts and cultures is also required socially. This is both, a joyful message and a warning. On the one hand, the comparison of the scripts and cultures is very promising and important for science and society. In science, alternative influencing factors and further similarities and early cultural contacts and connections can be discovered. This can set a lot of things in motion in society in terms of self-discovery, integration and international understanding.

At the same time, a warning must be sounded. For the previous seperation and neglect of comparing cultures and their similarities led to the intensification of exclusive cultural images, which ultimately resulted in racism and at last escalated into the catastrophe of the Nazi Germanic ideology, the Holocaust and World War II.

In this sense, there is an urgent need to tackle the comparison of the scripts and culters in Eurasia. Espacially early Turkic and „Germanic“.

Çağıl Çayır studied history and philosophy at the University of Cologne and is the author of „Runes in Eurasia. Über die apokalyptische Spirale zum Vergleich der alttürkischen und ‚germanischen‘ Schrift'“. He is the founder of „Kulturakademie Çayır“. His work has been published internationally in various science and mass media.

Çağıl Çayır studied history and philosophy at the University of Cologne and is the author of „Runes in Eurasia. Über die apokalyptische Spirale zum Vergleich der alttürkischen und ‚germanischen‘ Schrift'“. He is the founder of „Kulturakademie Çayır“. His work has been published internationally in various science and mass media.

Also interesting

– History –

Findings in Denmark: Was Germanic-God „Odin“ a Turk?

In 2020, a treasure hunter unearthed a magnificent gold treasure in a village called Vindelev in Denmark, dating from the mid-5th century, right from the middle of the Migration Period.